50, 3, 0, 4, 143, 143, 1, 1, 1, 0, 12, 8, 0

Save as PDF

| About |

Ode to Construction – Abstraction in the digital age is an

investigation into the visual strategies and ideologies of early

20th century Suprematist and Constructivist art movements from the

viewpoint of graphic designer and artist Polina Joffe. The

experiments resulted in the creation of a generative web

application, where constructions that echo modernist abstraction

can be made with the click of a button. Visitors are urged to play

with the generator and create their own constructions, with the

ability to save their artworks in high definition.

“We no longer write. We process words, by manipulating the electrical signals that govern simulated alphanumeric text on screens. We no longer draw. We process images, by manipulating electrical signals that govern simulated geometry on screens…The age of orthography has drawn to a close.” – John May, 2019 |

| Shop |

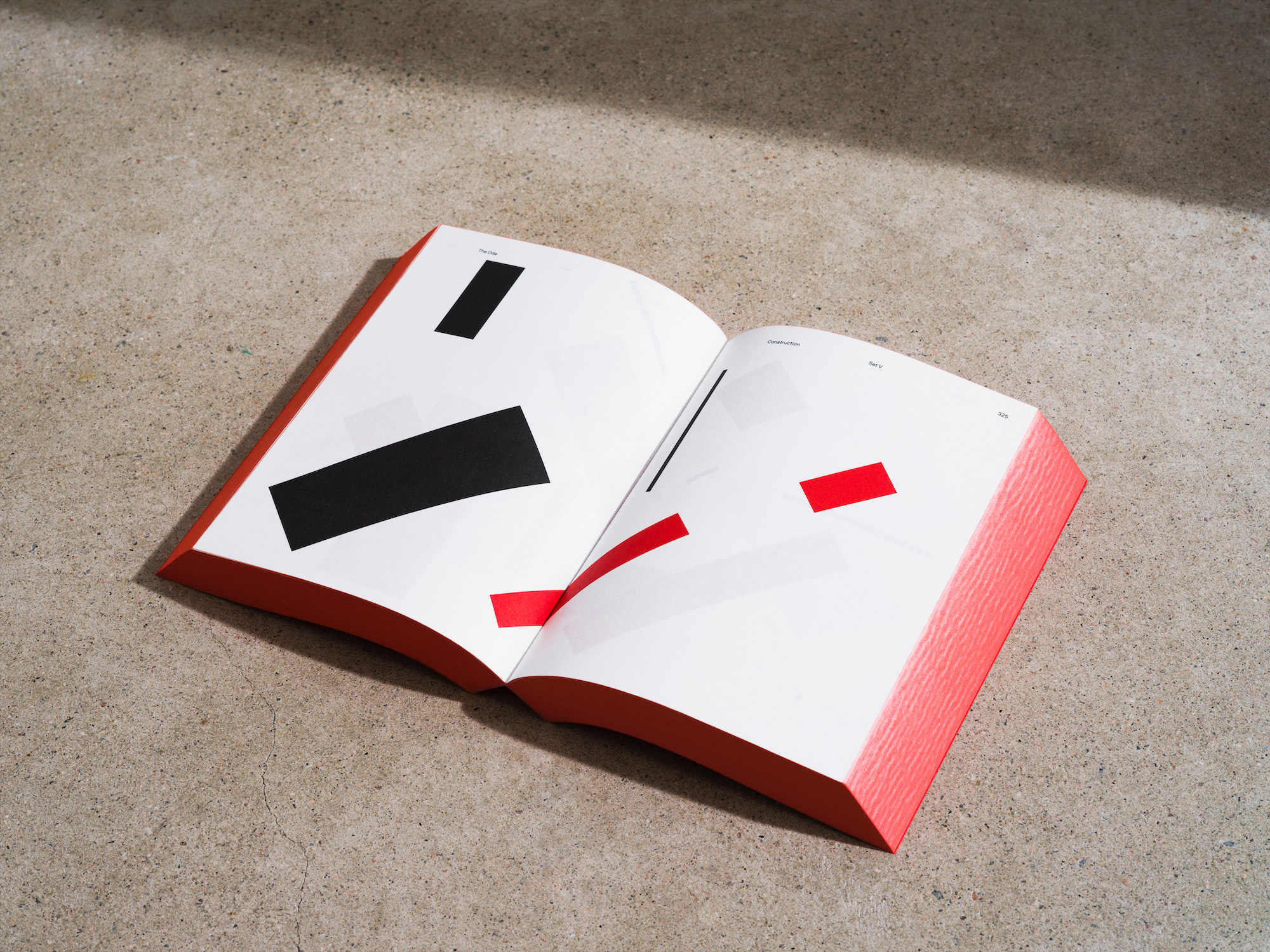

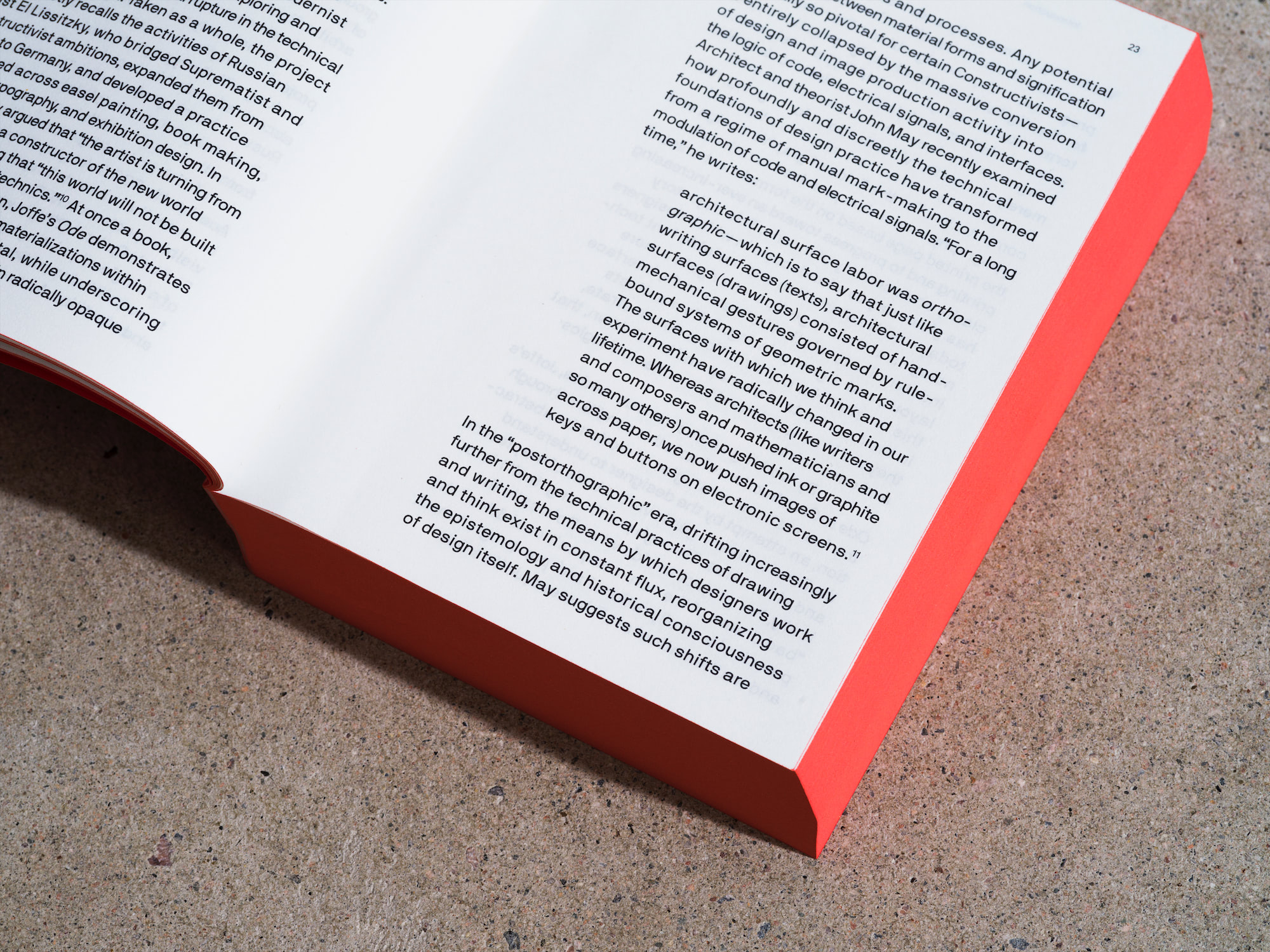

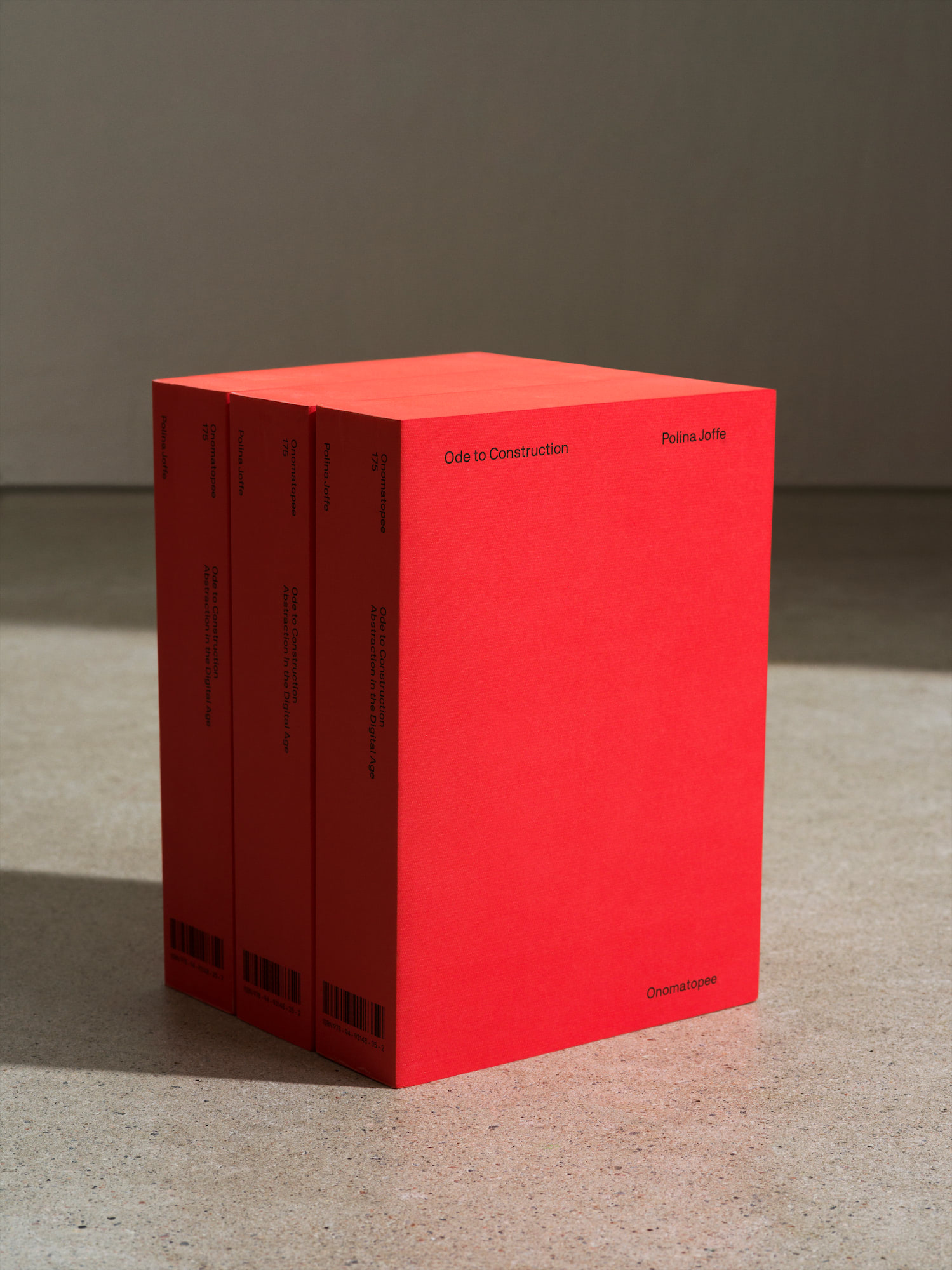

Onomatopee 175, Polina Joffe 25€ A chunky artist’s-book homage to the Russian Avant-garde that probes the fluidity of screen and print. This dynamic book is a graphic investigation into the Russian Suprematism and Constructivist movements, demonstrating the fluidity of design in the digital age. With a text contribution by Madeleine Morley and Max Boersma. Purchase prints

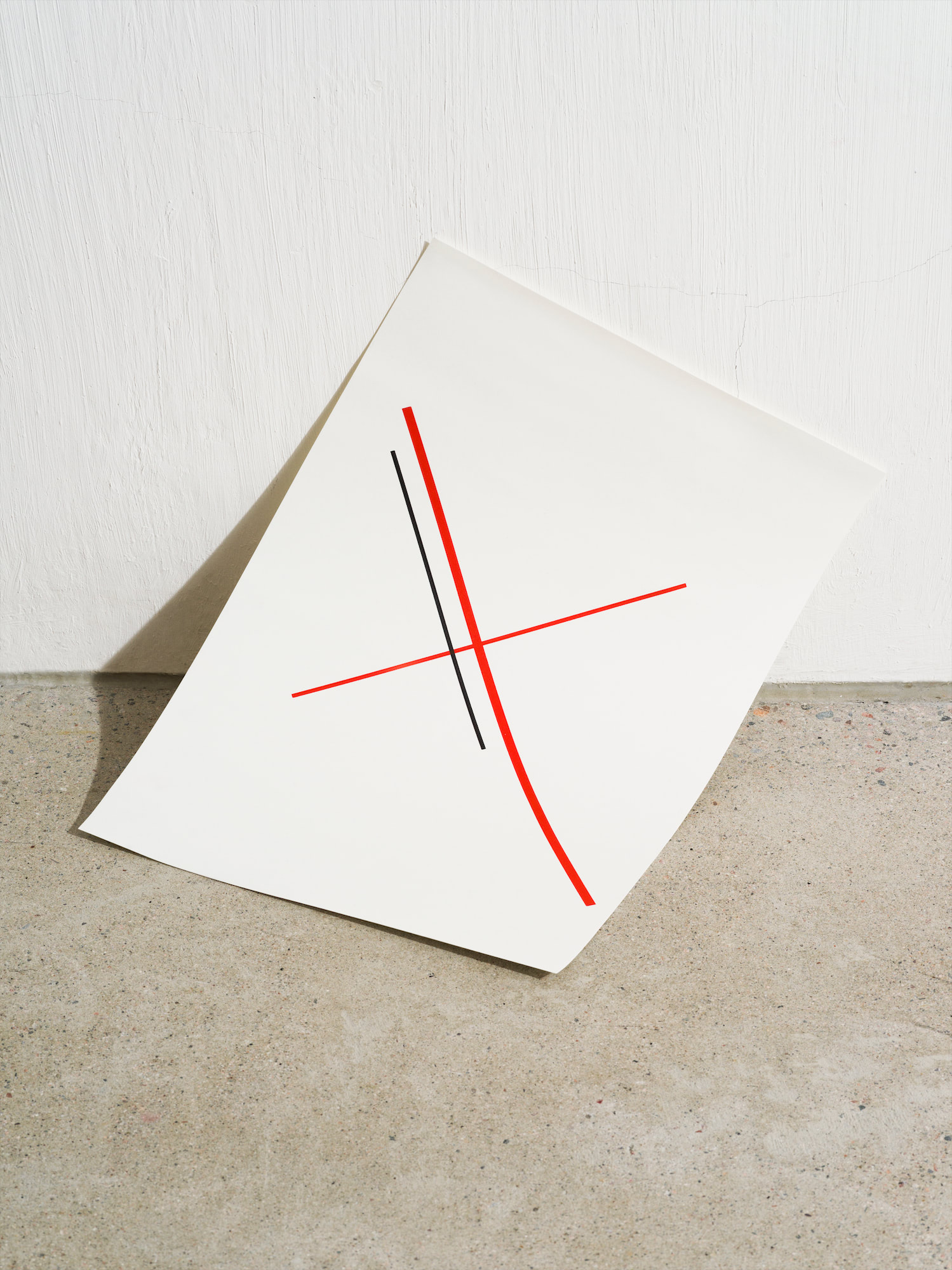

A2 Risograph print EOS 60/120 grams, off white Edition of 10 50€

A2 Risograph print EOS 60/120 grams, off white Edition of 10 50€

A3 Risograph print EOS 60/120 grams, off white Edition of 10 35€

A3 Risograph print EOS 60/120 grams, off white Edition of 10 35€

A3 Risograph print EOS 60/120 grams, off white Edition of 10 35€ You can purchase the prints directly from the artist by contacting them directly. When doing so please mention the following: Full Name Delivery Address Name of the prints you would like to order How many prints you would like Payment can be sent through PayPal to contact@polinajoffe.com |

| Installation |

Constructed from pixels and data, transformed into vector files, travelling through the cloud to an offset printer, and translated into physical metal objects, Ode to Construction – Abstraction in the Digital Age, moves effortlessly between screen, print, and space and simultaneously questions its context and medium. The installation shows a translation of pages 488-489 from the Ode to Construction book, traversing from code to print to spatial objects. First presented at Onomatopee Projects in Eindhoven, Netherlands between October – November, 2020. Architect: Kaisa Karvinen Production: Studio Remy Generative code: Leonid Joffe, Frederic Marx Curation: Joannette van der Veer Photography: Wibke Bramesfeld |

| Artist Letter |

Polina Joffe

Ode to Construction began as an investigation into the

visual strategies and ideologies of Russia’s Suprematist and

Constructivist movements. I call it an “ode” for several reasons,

but primarily because I’m referencing the love affair design has

had with the aesthetics of modernism for decades, including my own

love affair. My ode—somewhat melancholically, and also as an

homage—examines these historic movements from a contemporary

graphic designer’s viewpoint; it’s an ode to the idealism of the

Russian avant-garde, to a utopian notion of transforming art into

a medium that serves everyone, to the collapsing of distinctions

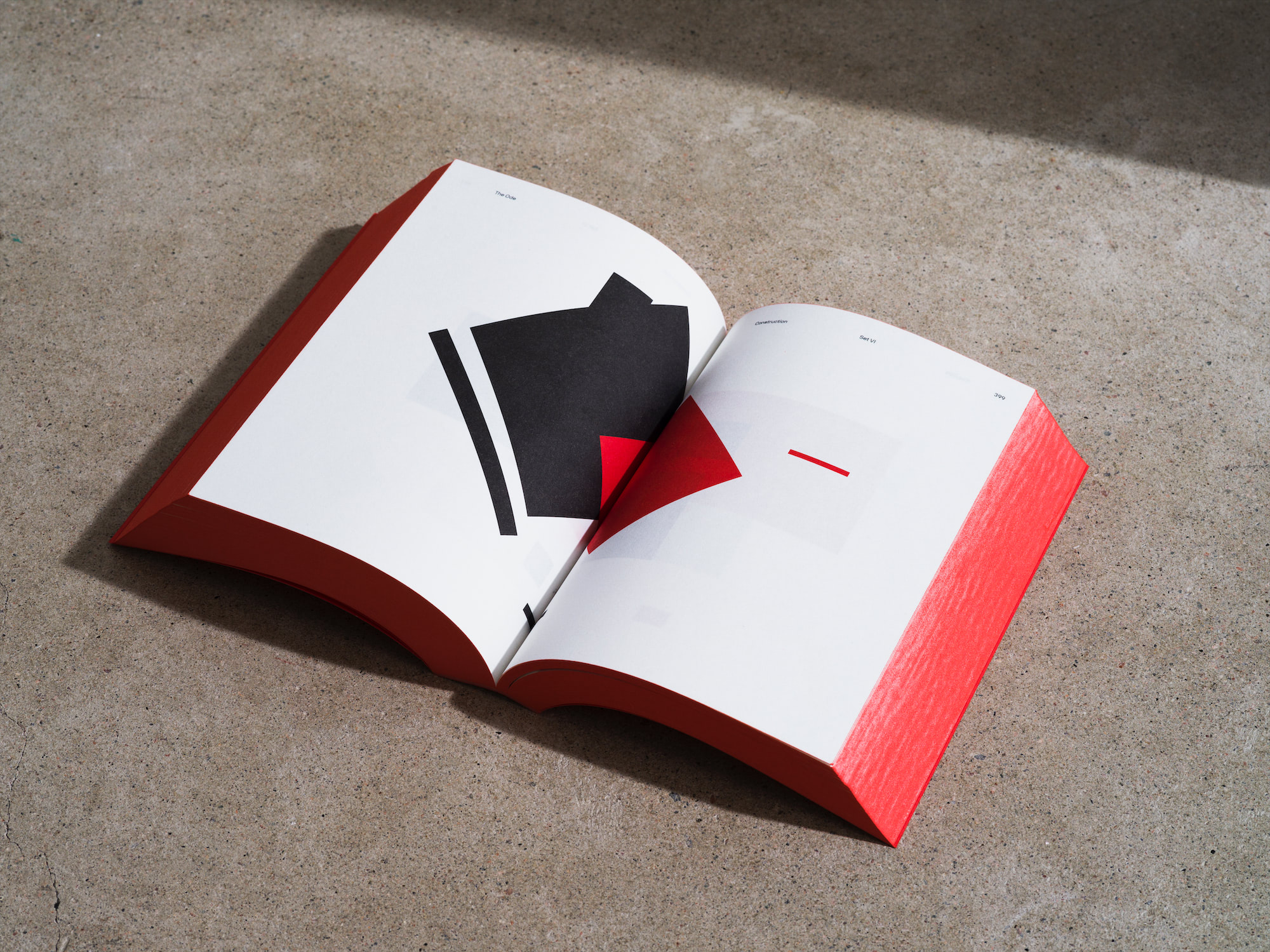

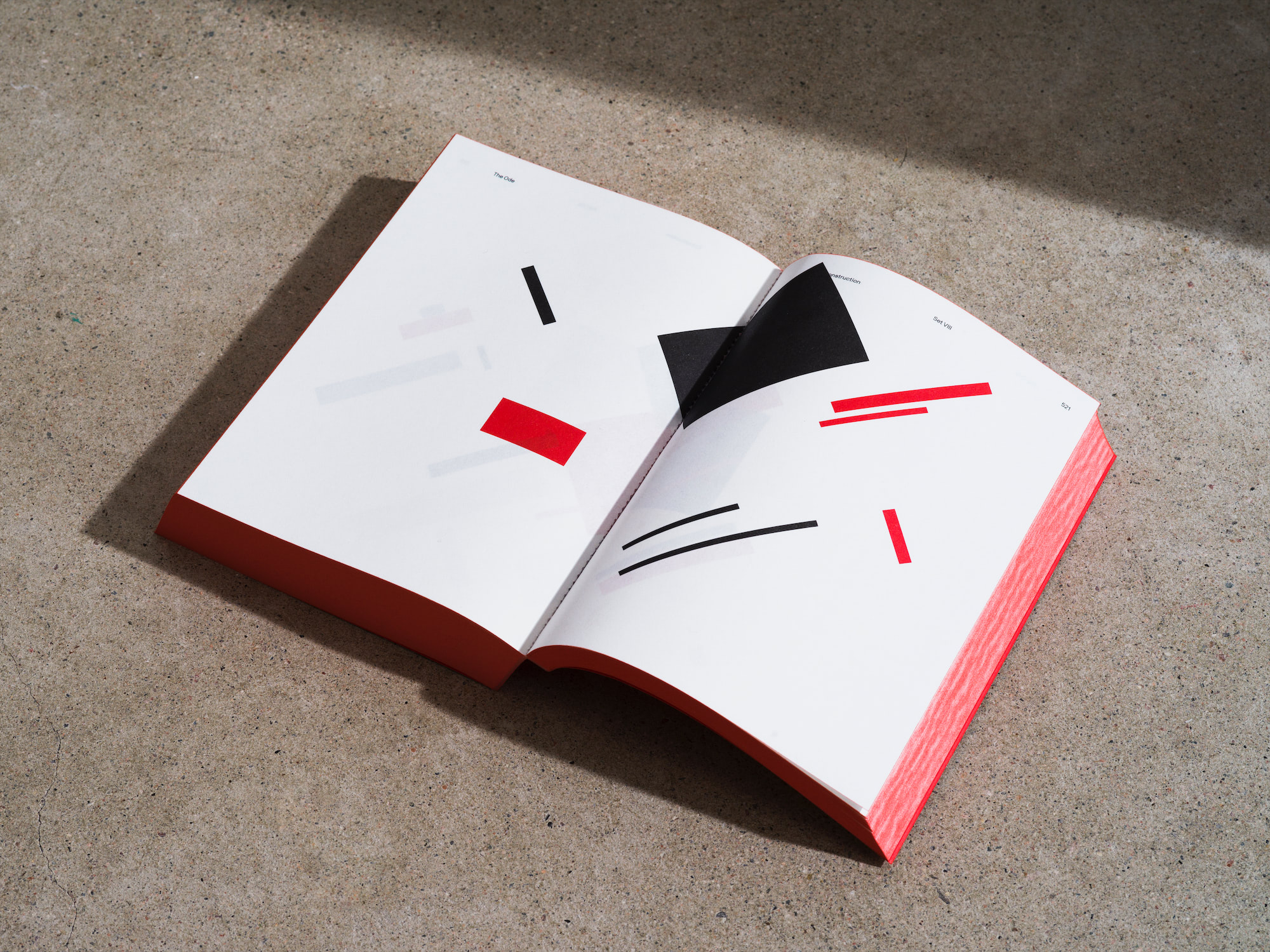

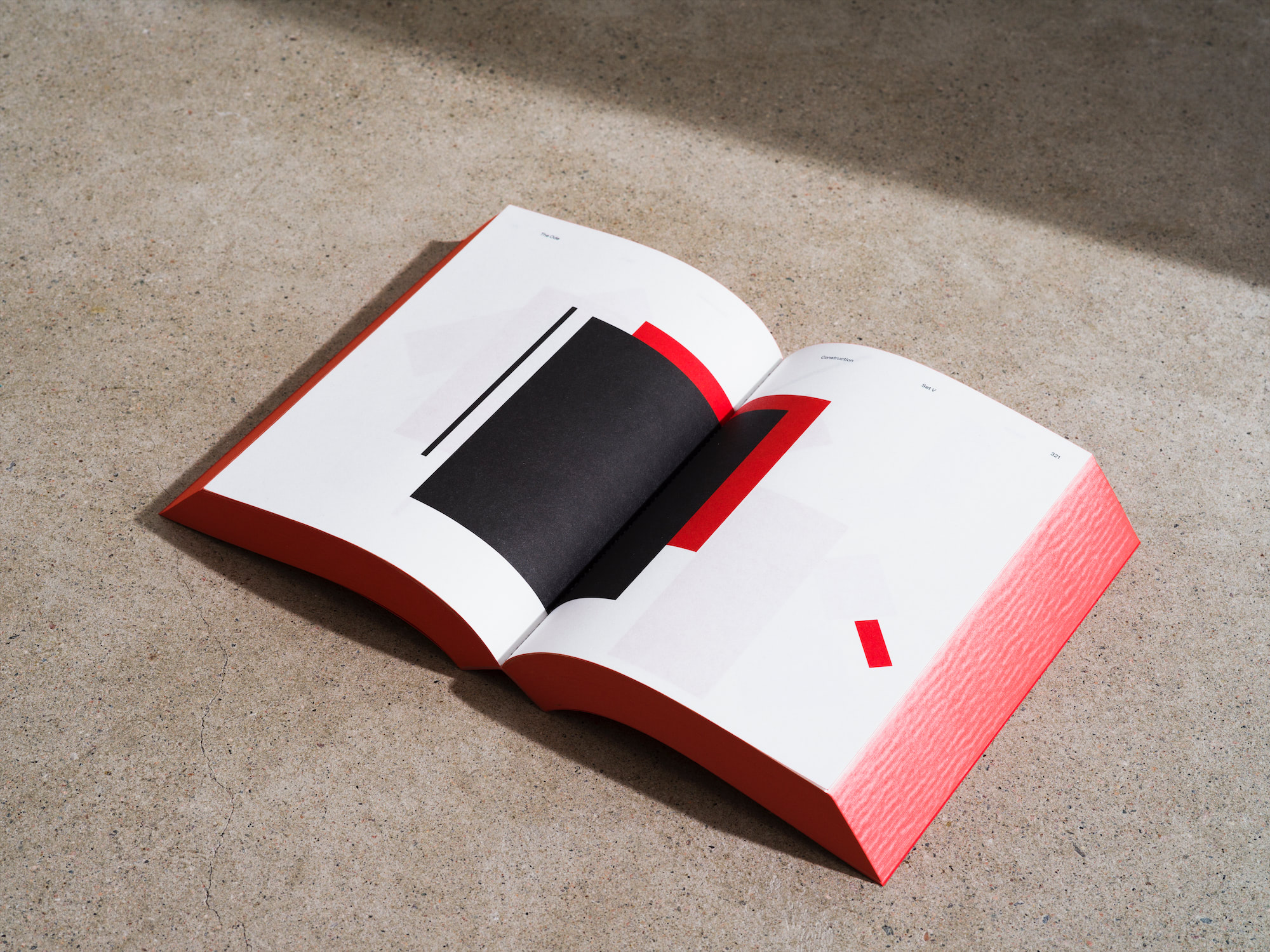

between art and design. For my ode, I’ve designed a generative

tool to automatically create constructions of red and black

rectangles, which stylistically echo modernist abstraction. With

this program, available at odetoconstruction.com, users can create

their own free “artworks” with the click of a button. This book

features generated outcomes of this digital tool.

Constructed from pixels and data, transformed into vector files, forming electric light beams on the screen before travelling through the cloud to an offset printer to become two inks on paper, the constructions in this book began life in one medium and ended in another. Similarly, the project’s accompanying exhibition (taking place at Onomatopee Projects in Fall 2020) features forms generated from code, but materialized as a temporary installation. My primary interest is in inviting the audience to question medium and context: What happens when a construction moves from code to print, or from code to space? What gets lost? What stays the same? I myself come to this history from my perspective as a graphic designer, working with print, typography, space, and shapes every day. Having left Russia for Finland as a two-year old before the fall of the Soviet Union, the forms of Russian abstraction have followed me throughout my life like a shadow. Ode to Construction’s color palette is red, white, and black, and therefore it references the aesthetics of the movements with which I’m engaged. But the colors also reference the lexicon of typography, and the typographic standard of black on white with red is an accent colour. For designers like myself, this palette is often the starting point. So it became the starting point for me here too. |

| Elergy to Construction |

Max Boersma and Madeleine Morley

“The artist is turning from an imitator into a constructor of the

new world of objects. This world will not be built in competition

with technics.”

– El Lissitzky, 1920 For modernist artists of the early 20th century, few concepts held as much potential as “construction.” The term and its synonyms, first gaining special prominence in writings about Paul Cézanne and the Cubists, promised to describe what was distinct and innovative about modernist painting.1 In the circles of Suprematism and certain abstract artists, the idea of “constructing” a work quickly came to oppose almost everything that had previously defined Western painting: academic notions of skill and beauty, bourgeois and aristocratic taste, the pictorial conventions of mimetic representation, and the understanding of the work of art as the expressive product of an artist’s individual subjectivity. “The artist can be a creator,” Kazimir Malevich wrote in 1915, “only when the forms in his picture have nothing in common with nature. For art is the ability to create a construction that derives not from the interrelation of form and color and not on the basis of aesthetic taste in a construction’s compositional beauty, but on the basis of weight, speed, and direction of movement. Forms must be given life and the right to individual existence.”2 In short, the artist should no longer seek to depict or imitate, but instead to build or construct, surrendering her own expressivity for that of the forms, materials, and principles with which she works. It was in post-revolutionary Russia that “construction” received its most vigorous scrutiny. Between January and April of 1921, the famous “Composition-versus-Construction” debate in Moscow aimed to define these antithetical concepts, gathering together painters, sculptors, architects, and critics for the task. A great deal was at stake: many participants viewed the establishment of this distinction as necessary for justifying the existence of artists within socialism and articulating their roles in a new egalitarian society and culture; without it, art itself would need to be abandoned in favor of activist organizing or industrial work. The group largely agreed on the negative attributes of “composition”—arbitrariness, hierarchy, and superfluity, all marks of subjective taste and, by implication, capitalism and its ways of life. The meaning of “construction,” however, proved elusive in both theory and practice. Formed from these meetings, the Working Group of Constructivists—among them artists Karl Ioganson, Varvara Stepanova, and Aleksandr Rodchenko—endeavored to unite formalism and materialism in their experiments in non-objective painting, sculpture, drawing, and collage. Art historian Maria Gough, in her meticulous examination of the Moscow debate, concludes that “the problem of construction is, in short, a problem of motivation: how to prevent this newly emancipated painterly content from free-falling into the merely arbitrary arrangement of random pictorial elements.”3 The Constructivists located their initial activities in an unstable space between art, science, engineering, and industry, positing the artist as an inventor of new forms and principles of organization.4 As such, the group’s activities moved toward increasingly rationalized, modular, and permutational logics, seeking to grasp and firmly anchor the technical principles of their making. Much of their experimentation, scholar Devin Fore suggests, embraced a misguided dichotomy between matter and writing. By positing material forces and signification as diametrically opposed, several participants adhered, in Fore’s words, “to a world view that categorically distinguishes between phenomenal experience and language.”5 These artists sought to identify their work solely with material principles, resisting any links to conventional meaning and referentiality. The “Composition-versus-Construction” debate ultimately broke off without a consensus, and the Constructivist group redirected its activities away from strictly formal experimentation into engagements with industry and new media forms. This second “Productivist” phase of Constructivism—encompassing textile production, photography, magazines, advertising design, posters, book making, and more—generated the movement’s most iconic works for the history of design.6 Typography and graphic design proved especially vital and enduring platforms for bridging Constructivism’s formal investigations and everyday life, communicating and engaging with a broader public.7 Meanwhile, the idea of construction migrated and transformed: A loose-affiliated network of “International Constructivists” stretched across Central and Eastern European, crossing with the Bauhaus, De Stijl, and Dada and stimulating a rich production of artist-run journals, typographic experiments, and exhibition designs. The rise of Hitler in Germany and Stalin in the Soviet Union interrupted this fervent period of creative activity, placing many artists under persecution and forcing others into exile. Following the second World War, as art historians, critics, and artists—slowly and imperfectly—learned of these interwar practices, Constructivist principles resurfaced in novel ways across the Americas, particularly in the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements in Brazil and literalist and Minimalist practices of the US. Radically condensing its activities, two broad contributions of Constructivism to the history of art and design can be observed: on the one hand, the movement proposed a rigorous formal,1 material, technical, and social analysis of the work of art; on the other, it championed a transformation of art’s distribution forms, working across media formats and circumventing the distinction between art and design.8 Polina Joffe’s Ode to Construction takes up this ubiquitous modernist term, its forms, and its legacy within altogether distinct technical and social conditions. The project stems from her longtime preoccupation with the Russian avant-garde in her work as a graphic designer, motivated in part by her birth in the late Soviet Union. To produce her book, Joffe employed a simple system of “construction variables,” which were written into a custom-coded program. These parameters allowed the automatic generation of each printed spread, modulating the dimensions, positioning, color, and number of forms within probabilistic numerical constraints. Listed at the outset of each section, the pre-given variables for the book’s ten “Construction Sets” demonstrate both the system’s formal variability and its dramatic reduction of Joffe’s input as a designer. In this way, her Ode reanimates many of abstraction’s strategies of “non-composition,” a term coined by art historian Yve-Alain Bois to describe a group of frequently recurring formal devices and techniques—central to the history of modernist abstraction—that bear a “programmatic insistence on the nonagency of the artist.”9 Encompassing both Suprematist and Constructivist practices, Bois’s category includes the grid, deductive structures, and the monochrome, as well as the collapse of figure/ground distinctions and the systematic deployment of process and chance. Joffe’s constructions arbitrarily shuffle and combine these formal and procedural tropes; however, her decision to constraint color to only red and black firmly weds the project not only to her practice as a book designer, working with the typographic lexicon of black, accent red, and white page, but to the legacy of the Russian avant-garde as well. This deliberate citational gesture sets Joffe’s book subtly apart from other recent artist’s books preoccupied with abstraction and the digital, in particular Tauba Auerbach’s RGB Colorspace Atlas (2011), a three-book set that attempts to spatialize the entire visible spectrum in RGB gradients, and Gerhard Richter’s Patterns (2011), in which a digital image of a single oil painting by the artist is submitted to sequential operations of division, mirroring, and repetition. Across its ten sets and 620 pages, Ode to Construction performatively undercuts—albeit affectionately—historical attempts to reach a degree zero of form or a final determination for “construction.” Joffe’s program, now available as an online platform, likewise gestures towards the desires of Suprematism and Constructivism to build a new, revolutionary mass culture; with a single click, the site produces new constellations instantaneously, each iteration downloadable as an image file and printable at home. Finally, the project’s exhibition form likewise engages with the historical shift of many Russian artists from two-dimensional painting into constructions in space, including novel display typologies and exhibition structures. In Joffe’s Ode, the formal strategies and devices of Constructivism and modernist abstraction become a means of exploring and articulating a deep historical rupture in the technical registers of design. Taken as a whole, the project most directly recalls the activities of Russian artist El Lissitzky, bridged Suprematist and Constructivist ambitions, expanded them from Russia to Germany, and developed a practice that moved across easel painting, book making, graphics, typography, and exhibition design. In 1920, Lissitzky argued that “the artist is turning from an imitator into a constructor of the new world of objects,” adding that “this world will not be built in competition with technics.”10 At once a book, website, and exhibition, Joffe’s Ode demonstrates the fluidity of a project’s materializations within the conditions of the digital, while underscoring the designer’s enmeshment in radically opaque technical systems and processes. Any potential opposition between material forms and signification—initially so pivotal for certain Constructivists—is entirely collapsed by the massive conversion of design and image production activity into the logic of code, electrical signals, and interfaces. Architect and theorist John May recently examined how profoundly and discreetly the technical foundations of design practice have transformed from a regime of manual mark-making to the modulation of code and electrical signals. “For a long time,” he writes: architectural surface labor was orthographic—which is to say that just like writing surfaces (texts), architectural surfaces (drawings) consisted of hand-mechanical gestures governed by rule-bound systems of geometric marks. The surfaces with which we think and experiment have radically changed in our lifetime. Whereas architects (like writers and composers and mathematicians and so many others) once pushed ink or graphite across paper, we now push images of keys and buttons on electronic screens.11In the “postorthographic” era, drifting increasingly further from the technical practices of drawing and writing, the means by which designers work and think exist in constant flux, reorganizing the epistemology and historical consciousness of design itself. May suggests such shifts are occurring almost daily and nearly imperceptibly with the technical intensification of design’s programs, tools, and algorithms. The words used for the digital products of design practices—terms like “drawing,” “model,” “type”—rely on anachronistic material associations to describe images on interfaces, which themselves exist merely as familiar visualizations for ongoing, real-time processes of numerical calculation and computation. For the fields of graphic design and typography, modernism promised to rationalize the printed page based on the formal mechanics of printing and to progress toward an ever-increasing clarity and economy of means. This trajectory has given way to a landscape in which designers today—with automation and variable font technologies at their fingertips—navigate a more indeterminate relation between code, interface layout, and digital printing. Joffe manifests this tension: Her constructions demonstrate, in their moments of overlap and breakdown, that they are in no way bound to mechanical logics and constraints. By working across various modes, Joffe’s Ode to Construction refracts this condition through the foundational strategies of modernist abstraction, an attempt by the designer to understand the Russian avant-garde via the tools of the present, and vice-versa. Through positioning itself historically, her project avoids what Bois calls the “bad dream of the non-compositional drive,” the pursuit of a wholly rationalized, pre-programmed, and mathematical art.12 Instead, Joffe’s Ode might be understood as an elegy for “construction,” recognizing both the promises and contradictions embedded in this historical term. In so doing, her project brings one apparent historical rupture in conversation with another to see what becomes visible and thinkable in the process. [Opening quote] El Lissitzky, “PROUN: Not world visions, BUT – world reality (1920),” in El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 347. Translation modified. 1 To cite just one example of this discourse, the Cubist painters Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger wrote in their influential 1912 book On “Cubism” that “the act of composing, constructing, designing, can be reduced to this: to regulate, through our own activity, the dynamism of form.” Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, “Du ‘Cubisme’ (Paris: Eugene Figuiere, [27 December] 1912),” in Patricia Leighten and Mark Antliff, eds., A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 424. 2 Kazimir Malevich, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism (1915),” in John Bowlt, ed., Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1988), 122–23. 3 Maria Gough, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 27. In the first chapter of her book, entirely devoted to the “Composition-versus-Construction” debate, Gough differentiates several competing solutions proposed by artists to the problem of “construction,” examining both textual sources and a portfolio of works on paper produced by the participants, which attempted to demonstrate the two terms. Along with Christina Kiaer, Gough was among the first group of researchers in art history to gain access to Russian archives after the fall of the Soviet Union, uncovering documents and sources either long inaccessible or entirely unknown to previous scholars. 4 For a recent exhibition that examines the various redefinitions of the artist’s role in this period, see: Jodi Hauptman and Adrian Sudhalter, eds., Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented: 1918-1938 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2020). 5 Devin Fore, “The Operative Word in Soviet Factography,” October 118 (Fall 2006): 99. Fore places Rodchenko, Stepanova, and Osip Brik within this group, while suggesting that other participants held less dualistic positions, including Aleksei Gan, Boris Kushner, Liubov Popova, and Nikolai Tarabukin. 6 For a study of this second phase, tracking several of Constructivism’s attempts to engage and shape a socialist consumer culture, see: Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005). 7 Focused on the work of Constructivist theorist and activist Aleksei Gan, art historian Kristin Romberg recently proposed that, in fact, “the model of material-making that most informed constructivism was typographic printing, rather than the sculptural model assumed by existing scholarship.” While her use of the superlative perhaps advances an unnecessary distinction, Romberg’s project brings newfound focus to the labor and thinking behind Gan’s typographic work. Kristin Romberg, Gan’s Constructivism: Aesthetic Theory for an Embedded Modernism (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 109. 8 In a pivotal essay, Benjamin Buchloh presents a critical mapping of Russian and Soviet avant-garde activities, passing from formal experiments with painterly faktura into practices of photomontage, before arriving at the proto-documentary strategies of factography—a series of shifts driven by a search for new modes of mass cultural engagement and conditions of “simultaneous collective reception.” Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October 30 (Autumn 1984): 83–119. 9 Yve-Alain Bois, “Abstraction, 1910–1925: Eight Statements.” October 143 (Winter 2013): 8. 10 El Lissitzky, “PROUN: Not world visions, BUT – world reality (1920),” in El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 347. Translation modified. 11 John May, Signal. Image. Architecture. (Everything is Already an Image) (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019), 33. 12 Bois elaborates on this “bad dream” as follows: “Initiated by Theo van Doesburg in 1930, shortly before his death, this so-called ‘mathematical’ tendency in art was developed by the Swiss artists Richard-Paul Lohse and Max Bill in the late ’30s. In looking at the dull portfolio of Fifteen Variations on a Single Theme, published by Bill in 1938, one cannot but think of Adorno’s condemnation of serialism, even in the late work of his hero Schoenberg, as the defeat of art in its fight against the rationality of the administrated world and the bourgeois ideal of a global domination of nature. And it is not only a defeat, claims Adorno, but a total surrender, an ultimate reconciliation. The agency of man has indeed been effaced in such an art, but the negativity of the non-compositional impulse, geared towards the erasure of the artist as the bourgeois dominator of his material, has produced the author as slave of the authoritarian system of rationalization that his fight was designed to combat.” Bois, 8. |

| Further Reading |

Suprematism and El Lissitzky

Bois, Yve-Alain. “El Lissitzky: Radical Reversibility.” Art in America 76, no. 4 (April 1988): 160–81. Borchardt-Hume, Achim, ed. Malevich. London: Tate Publishing, 2014. Clark, T. J. “God is Not Cast Down.” In Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, 225–297. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. Gough, Maria. “Constructivism Disoriented: El Lissitzky’s Dresden and Hannover Demonstrationsräume.” In Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow. Edited by Nancy Perloff and Brian Reed, 77–128. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2003. Lampe, Angela, ed. Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-garde in Vitebsk, 1918–1922. Munich: Prestel, 2018. Constructivism Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. “From Faktura to Factography.” October 30 (Autumn 1984): 83–119. Gough, Maria. The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Hauptman, Jodi, and Adrian Sudhalter, eds. Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented: 1918–1938. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2020. Kiaer, Christina. Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005. Witkovsky, Matthew S., and Devin Fore, eds. Revoliutsiia! Demonstratsiia!: Soviet Art Put to the Test. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017. Modernist Abstraction Bois, Yve-Alain. Painting as Model. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990. Dickerman, Leah, ed. “Abstraction, 1910–1925: Eight Statements.” October 143 (Winter 2013): 3–51. Dickerman, Leah, ed. Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012. Gough, Maria. “Frank Stella Is a Constructivist.” October 119 (Winter 2007): 94– 120. Small, Irene V. Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Graphic Design and Typography Drucker, Johanna. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York: Granary Books, 2004. Eisele, Petra, Isabel Naegele, and Michael Lailach, eds. Moholy-Nagy and the New Typography: A–Z. Bönen: Verlag Kettler, 2019. Gough, Maria. “Contains Graphic Material: El Lissitzky and the Topography of G.” In G: An Avant-Garde Journal of Art, Architecture, Design, and Film, 1923- 1926, edited by Michael Jennings and Detlef Mertins, 21–51. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2010. Lavin, Maud. Clean New World: Culture, Politics and Graphic Design. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001. Pater, Ruben. The Politics of Design: A (Not So) Global Manual for Visual Communication. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2016. Digital Media Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018. Drucker, Johanna. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014. Gaboury, Jacob. “Hidden Surface Problems: On the Digital Image as Material Object.” Journal of Visual Culture 14, no. 1 (2015): 40–60. Hayles, N. Katherine. Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017. May, John. Signal. Image. Architecture. (Everything is Already an Image). New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019. |

| Credits |

Concept and design

Polina Joffe Website Frederic Marx Simon Wilson Construction generator Frederic Marx Leonid Joffe Elegy to Construction authors Max Boersma Madeleine Morley Typeface NB International Pro Stefan Gandl, Neubau Photography unless otherwise stated Lina Jelanski, Duotone Supported by Arts Promotion Centre Finland Grafia |

| Privacy Policy |

Ode to Construction

© Polina Joffe, 2021 Legal Disclaimer The contents of these pages were prepared with utmost care. Nonetheless, we cannot assume liability for the timeless accuracy and completeness of the information. This website contains links to external websites. As the contents of these third-party websites are beyond our control, we cannot accept liability for them. Responsibility for the contents of the linked pages is always held by the provider or operator of the pages. Data Protection When visiting the Ode to Construction website, no personal data is saved. We point out that in regard to unsecured data transmission in the internet (e.g. via email), security cannot be guaranteed. Such data could possibly be accessed by third parties. Copyright Contents and compilations published on these websites by the providers are subject to German copyright laws. Reproduction, editing, distribution as well as the use of any kind outside the scope of the copyright law require a written permission of the author or originator. Downloads and copies of these websites are permitted for private use only. The commercial use of our contents without permission of the originator is prohibited. Copyright laws of third parties are respected as long as the contents on these websites do not originate from the provider. Contributions of third parties on this site are indicated as such. However, if you notice any violations of copyright law, please inform us. Such contents will be removed immediately. |